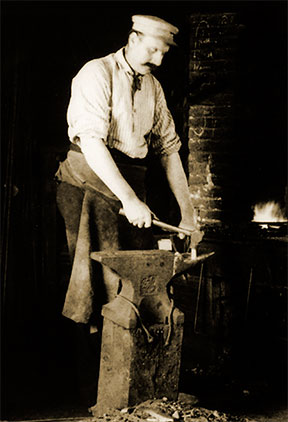

The village blacksmith—he is the big man in a sleeveless leather vest, sweating in a way that makes his forehead and biceps stare back at you, yet friendly as the milkman or local parson. He is the man you call when facing the impossible emergency down on the farm or shop.

The poet Longfellow imprinted his image permanently within the American consciousness through his 1840 poem “The Village Blacksmith”:

Under a spreading chestnut-tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His hair is crisp, and black, and long,

His face is like the tan;

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns whate’er he can,

And looks the whole world in the face,

For he owes not any man.

The trade name comes from two words, black and smythe. The former refers to the dark oxides that form over heated metal; the latter comes from what the craftsman did day by day—smite the metal to create its shape. Everyone in town knew what the smith was about, and many would stand by during an idle hour waiting and watching the magician at work. The early smiths held a high place in the village because their work required grit, steadiness, and business sense, and because it evolved around the two necessities of rural and small-town life, tools and travel.

The shop typically stood at the corner of the town’s two main roads, and so was a logical social center, despite the constant clanging and the heat from the forge. Historical journals from shop apprentices most often mention the monotony and physicality of the trade, as well as its curious appeal.

The earliest smiths worked mostly in bronze and iron. Later the iron was alloyed with carbon for steel as a cheaper option to mend or replace that damaged axle or farm tool. The smiths required creative intellect to achieve mastery of the craft in an age that predated custom replacement parts and required instead that wagons, equipment and tools be repaired by the shaping and reshaping and bonding of metals. Hinges, sleigh runners, and horseshoes did not originally come in boxes.

The shops would be as uniform from town to town as the local schools or churches. The centerpiece was the forge, made from bricks and most often stoked with coal. Nearby would be a large bellows required to regulate the heat of the fire. Then came the iron anvil upon which the smith would go about smiting the burning metal to bring it to shape, and the vises used to hold the bars in place. Tongs and various hammers hung from the smoke-stained walls.

The methods employed by the village blacksmith have remained the same for centuries. Forging is the principle in which a heated metal is drawn and shaped upon an anvil to customize a fit. Opposite this procedure is upsetting in which a longer piece of metal is heated and compressed into a thicker shape by striking its ends—rivets are commonly made through this process. Then comes welding in which two pieces of metal are heated to white and thus made partially molten to the point where they can be joined with a few key blows of the hammer. Tempering is the method in which metal is hardened by heating it to a high degree and then plunging it into water for fast cooling and the procedure repeated. Beyond methods employing heat, a blacksmith would also shape and join metals through sawing, punching holes and riveting.

The late 19th-century industrial revolution began to relegate smithing to a specialty craft, and the village blacksmith would eventually be replaced by the auto repair shop or local engineering firm, and then the Sears catalog. The trade remained constant only in ranching country where smiths still shape brands and branding irons and keep horses in the correct shoes, sometimes working with local veterinarians in that latter enterprise.

WW 1 was the turning point. Manufacturing plants evolved to support of the war effort and on a mass scale, while the automobile and aviation industries developed alongside. And the larger enterprises swallowed the smaller. With this social change, village life changed irreversibly. The war moved families from their original settlements, as with more manufacturing always comes the exodus from the small town to the cities where steady wages are promised as a better option than the insecure economies of farm and village.

Many of the blacksmith shops that survived after the war did so by adjusting to the new challenges of trucks and cars. In Saginaw, Michigan, Barney Neumeyer opened his shop in 1925 with a focus on transportation and then became a key player in the war effort when metal and material shortages created a range of needs. He made replacement gears for the Saginaw Gear Plant and fenders for automobiles, while still also repairing a steady stream of farm implements.

Guilds across the country still offer support to smiths who specialize in ornamental work and more recently to the manufacture of high-quality knives or swords. And replicas of the old shops are preserved in historical displays as in Small Town, Mississippi, where visitors can peruse McIntosh Blacksmith Shop; likewise, at Anderson’s Blacksmith Shop in Williamsburg, Virginia, and at Small Town Forge in Grafton, Connecticut.

But the growth of cheap, industrially produced items after WW1 has pretty much relegated the image of the old smithy to Hollywood Westerns and television shows like Little House on the Prairie. He lives on principally in our cultural mythology.

Week in, week out, from morn till night,

You can hear his bellows blow;

You can hear him swing his heavy sledge,

With measured beat and slow,

Like a sexton ringing the village bell,

When the evening sun is low.

And children coming home from school

Look in at the open door;

They love to see the flaming forge,

And hear the bellows roar,

And catch the burning sparks that fly

Like chaff from a threshing-floor.

He goes on Sunday to the church,

And sits among his boys;

He hears the parson pray and preach,

He hears his daughter’s voice,

Singing in the village choir,

And it makes his heart rejoice.

It sounds to him like her mother’s voice,

Singing in Paradise!

He needs must think of her once more,

How in the grave she lies;

And with his hard, rough hand he wipes

A tear out of his eyes.

Toiling,–rejoicing,–sorrowing,

Onward through life he goes;

Each morning sees some task begin,

Each evening sees it close

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night’s repose.

Thanks, thanks to thee, my worthy friend,

For the lesson thou hast taught!

Thus at the flaming forge of life

Our fortunes must be wrought;

Thus on its sounding anvil shaped

Each burning deed and thought.