The generation is nearly gone that retains some memory of the milkman or his young “jumper”, lugging cartons of milk and cream from a paneled truck up and down the steps of his customers or perhaps placing the bottles inside the cubby that opened from both inside and outside the house to store the delivered product and keep it cold until taken in, also the place where old bottles were set.

Those who remember likely do recall the sound of the old milk truck rattling down the street, its dairy name written in block letters on the side. And a very few may still remember the days of the carts milkmen once pulled along the cobbly streets or dirt roads, pulled along by old horses in most cases, carrying with them the smell of barn and pasture, the delight of children. Some were even pulled by very burly dogs.

Those days are mostly gone, however, except in a few remote farm communities. In those bygone days you entered your neighbor’s house by the back door, the front saved for special occasions like births or weddings or deaths. The main family business took place on a large wooden table in the kitchen where it was always warm and where the matron’s treasured bric-a-brac decorated shelves and window ledges. The milkman was one of the more regular visitors to the kitchen, often starting the family’s day with a greeting of good cheer or news of the concerns of relatives and friends up the road.

The era of the old milkmen was cut short by the gradual movement away from farm communities. Children wanted a better education and more job or marriage prospects than the smaller farm communities offered. Larger farmers bought out the smaller. Then in the cities, density encouraged sprawl, and the sprawl received a push when public transportation allowed people to purchase or rent farther from the centers of town where they worked. Customers grew too far apart for the milkman to make his route profitable. He had to raise prices. Then competition came from the new grocery stores which boasted better methods of refrigeration and promised that their milk was pasteurized and homogenized and healthier, less inclined to spoil, and cheaper.

The typical milking cow can drink the equivalent of a bathtub worth of water in a day. That same cow will eat upwards of 100 pounds of feed daily, a combination of grass, hay, and some silage like soybean meal. If its feed is principally grass, that poundage will increase. Out of all that consumption, the cow milked three times a day will produce six to seven gallons of milk each day.

In 1915 Wisconsin would have had about 170,000 dairy farms of about 200 acres, all with cows producing gallons and gallons of milk. (Note for historical context that more recently the number of dairy farms in Wisconsin is down to about 9000.) Herd size has always been a matter of economics—how many cows can the farmer purchase and feed, especially given the level of their consumption. Still the volume of milk produced then and now is enormous.

The milk from the cows would be stored in large 55-gallon steel tanks. These would then be taken by cart to the co-op, maybe six per cart for the small farmer and his poor hack. In 1915 there would have been about 400 co-ops in Wisconsin. These co-ops allowed for a more consistent quality, pricing, and distribution to larger towns or cities like Milwaukee and Chicago. From the co-op, as well as the small independent farm, a great portion of the product would go to the butter and cheese factories to be poured into large rectangular vats for processing. Cheese production gave milk stability as refrigeration was difficult. Typically, refrigeration meant ice cut in chunks from frozen rivers and lakes or sometimes old ammonia refrigeration systems.

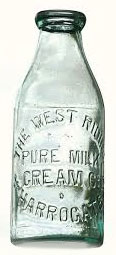

Bottling began with the first glass bottle patent in 1878, the Lester Milk Jar. In 1884 Henry Thatcher developed a system of producing bottles with a tight cap. Then came the various methods for etching a name into the glass. By 1915, many farmers had bottling capabilities on the farm and could go straight from farm to customer with the fresh milk. The farmers with this capability might have used a room off the main house or in a small out building for the enterprise. Otherwise bottling was done at plants connected to the co-ops or situated near clusters of independent dairy farms.

Many of the farmers producing milk for bottling in the early days resisted pasteurization, the process of heating and cooling milk to kill certain bacteria thought to produce tuberculosis and other diseases. It would eventually become standard practice at processing plants by the 1930s.

Homogenization was another matter, that being the pressurizing process that separates the fats from the raw milk. Though various machines were designed to do this by 1915, customers were slow to see the value as homogenization seemed to degrade the final product. Mass production and advertising won that war, however, and homogenization became the standard practice with the spread of large grocery chains in the 1950s.

The path of milk from the cow to the child’s glass has remained reasonably constant over the past century. The milk goes from utter to tank to storage facility–for separation into different products–to distributor to kitchen table. The difference between then and now is volume, of course, and the kind of refrigeration and purification processes employed in the storage facilities. And the diminished communal benefits. The milkman was not just a local entrepreneur—he was a symbol of all that made America a neighborly place.

A few companies like Illinois-based Oberweis Dairy have found success recently by offering “old-fashioned” milk deliveries and a healthier, more flavorful product than what the local Kroger offers. Oberweis advertises that in their milk the cream still rises to the top. But this is likely a retro trend that will pass in the inexorable push toward speed and convenience that drives the modern agenda. It is left for the historian to paint and preserve a picture of that older and more neighborly time.

Most milkmen through the twentieth century delivered a product in which the cream floated to the top. That may be the metaphor that tells the whole tale. Customers loved that layer of cream, and many now, sadly, have no memory of what the phrase even means.